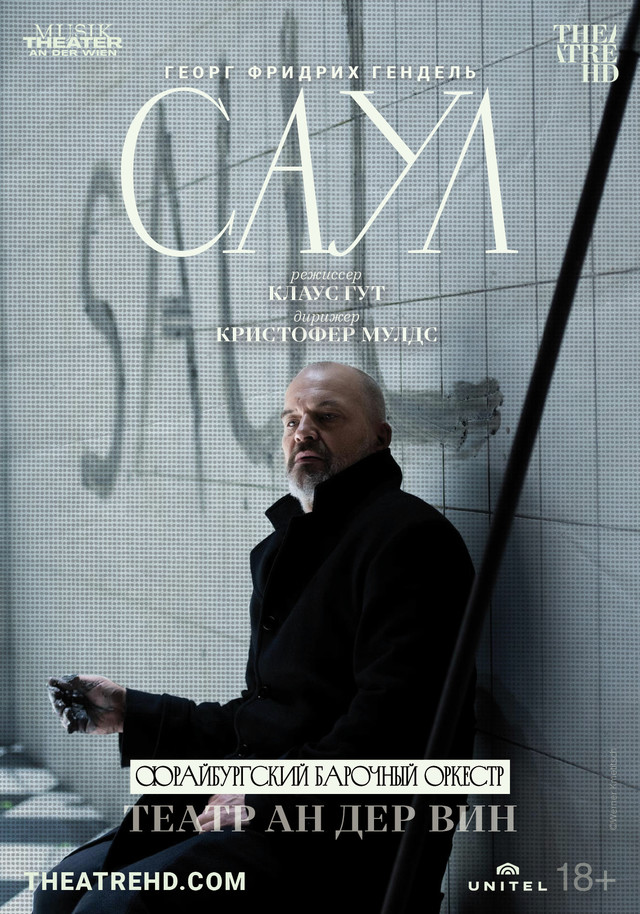

Theater an der Wien: Saul

Year: 2021

Country: Austria

Director: Claus Guth

Conductor: Christopher Moulds

Set designer: Christian Schmidt

Cast: Florian Boesch , Anna Prohaska, Giulia Semenzato , Jake Arditti, Rupert Charlesworth

Genre: opera

Runtime: 168 min.

Age: 18+

Country: Austria

Director: Claus Guth

Conductor: Christopher Moulds

Set designer: Christian Schmidt

Cast: Florian Boesch , Anna Prohaska, Giulia Semenzato , Jake Arditti, Rupert Charlesworth

Genre: opera

Runtime: 168 min.

Age: 18+

The pure Handel stroke of luck! (с)

George Frideric Handel had dominated musical life in London with his Italian-style operas ever since his sensational success with Rinaldo in 1711 – going broke twice in the process, incidentally. From the outset, however, there had been critics who demanded operas in English. By the end of the 1730s Italian operas had fallen entirely out of favour in London, so the composer looked for new ways of captivating his listeners. He began to experiment more extensively with English-language oratorios. In 1739, Saul marked the start of his new career. For Handel, oratorios in English had several advantages: He satisfied the opponents of Italian opera, did not have to pay the expensive fees commanded by Italian singing stars, and did not have to budget for opulent sets and costumes. Possibly to compensate for the lack of visuals, Handel scored Saul for remarkably rich and novel instrumentation: to begin with he used instruments that were thought at the time to have been used in the days of King David (1000 BC), such as trombones and extensive percussion. To this he added a harp, required by David’s use of one in the piece as a means of trying to soothe Saul, and a carillon, a set of bells played by striking a keyboard, that succinctly portrays Saul’s madness as the oratorio progresses. Furthermore, the structure of Saul still shows a great affinity with opera because unlike conventional oratorios there is no narrator. Instead, the characters speak to and across one another. These dramatic elements make it almost natural to present Saul not in concert form, as is traditional for an oratorio, but to think of it in terms of a staged production. In the 2017/18 season, director Claus Guth and his set designer Christian Schmidt grasped the nettle and created a highly acclaimed production that offers a lot of room for associations and thoroughly explores the titular character – just as Handel intended. The title role of the despairing King Saul who sees his power slowly diminishing will be sung by our artist in residence Florian Boesch, just as it was in 2018.